Muzikolog mezi filigrány / A musicologist swims in watermarks

Lenka Hlávková

(English translation below.)

Hudební prameny z období pozdního středověku, které se dochovaly v domácích knihovnách a archivech, jsou v mnoha ohledech „pole neorané“ nejen, co se týče stavu poznání jejich obsahu, ale také jejich hmotné podstaty. Pokud si zrovna některý badatel nevybral určitý rukopis k detailnímu monografickému studiu (nebo příslušný titul nebyl zadán studentovi hudební vědy jako východisko pro jeho diplomovou či disertační práci), i v době pokročilé digitální evidence filigránů máme k dispozici pouze přibližné informace o dataci většiny hudebních pramenů. V rámci projektu „Staré mýty, nová fakta“ se snažíme tento deficit odstranit alespoň u klíčových rukopisů, bez spolehlivé datace pramenů můžeme totiž jen těžko přicházet s novými poznatky historické povahy.

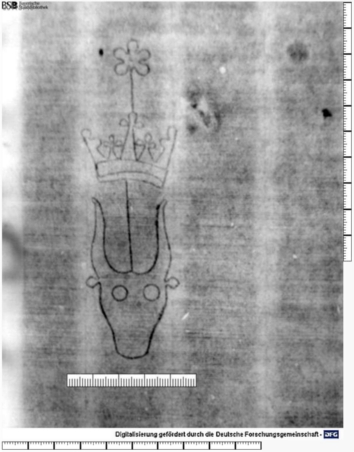

Ve dnech 1. – 4. července 2020 jsem se účastnila každoroční mezinárodní muzikologické konference Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference (místo v Edinburghu letos pouze ve virtuálním prostředí) a hned první den mě velmi zaujal příspěvek kolegů z mnichovské Bavorské státní knihovny. Tato instituce patří k předním průkopníkům digitalizace (nejen) hudebních pramenů a v nedávno realizovaném projektu Erschließung und Digitalisierung der Wasserzeichen in den Musikhandschriften der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek bis zum Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts vykročila směrem od zprostředkování obsahu hudebních rukopisů, které je dnes již zcela běžné, k digitálnímu zpracování jejich fyzické stránky. Řešitelé projektu Dr. Veronika Giglberger a Bernhard Lutz ve svém referátu informovali nejen o využití termografie při šetrném pořizování snímků, ale též o širším metodologickém rámci projektu. Každý rukopis z celkového počtu 170 byl nejprve podroben kodikologické analýze, což bývá jeden z hlavních důvodů, proč se badatelé dožadují expedování originálního pramene, a zároveň moment, kdy se dostává do konfliktu ochrana historického materiálu a potřeba jeho vědecké reflexe. V další fázi projektu proběhla digitalizace filigránů a po technickém zpracování následovalo propojení záznamů zveřejněných na stránkách Bavorské státní knihovny s existujícími databázemi (Wasserzeichen-Informationssystem, RISM). Veškeré informace o rukopisech jsou tedy dostupné online a srdce každého muzikologa, kterého jeho téma někdy přinutilo pustit se samostatně do kodikologického rozboru pramenů (a poněkud tak „lézt do zelí“ kolegům z pomocných věd historických), samým nadšením plesá.

Jak jsme na tom v Čechách? Zatím chodíme na filigrány s pauzákem, měkkou tužkou a lampou se studeným světlem. V lepším případě technicky zdatní kolegové fotografují a v rámci možností programů na úpravu fotografií ladí kontrasty tak, aby byl filigrán alespoň trochu vidět i pod hustě psaným textem. Přes značnou zručnost některých českých badatelů a pověstného kutilského ducha se ovšem tímto způsobem profesionální termografické snímky rozhodně nahradit nedají. Kdyby ovšem existovala databáze mapující výskyt filigránů v rukopisech (nejen hudebních) uložených v institucích v celé České republice, která by byla propojená s existujícími mezinárodními systémy a sbírala data s využitím stejné technologie, historicky orientované obory by tento krok jistě přivítaly. S přibývajícími záznamy v databázích lze nejen přesněji datovat příslušný rukopis, ale také získat více informací o jeho širším historickém kontextu. Pokud například v hudebním rukopise prokazatelně českého původu nalezneme papír italské výroby, naše úvahy se mohou ubírat různými směry. Dovezl si někdo papír z Itálie i s opsanými skladbami? Dal se tento papír v Čechách běžně získat? Nebo jeho výskyt souvisí s kontakty určité konkrétní instituce? Na takové otázky se snažíme hledat odpovědi i s pomůckami, které máme momentálně k dispozici, bylo by ovšem krásné, kdyby se podařilo zmenšit náskok našich bavorských sousedů a vyzkoušené postupy aplikovat i na české prameny. Romantické duše by sice mohly postrádat pravidelný rituál spočívající v nákupu zásoby průsvitného papíru (pauzáku) a kontrole stavu měkkých tužek před každou výpravou na „lov“ filigránů, české vědě by ovšem technologický pokrok v tomto ohledu jistě prospěl.

Odkazy:

Erschließung und Digitalisierung der Wasserzeichen in den Musikhandschriften der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek bis zum Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts

https://www.bsb-muenchen.de/ueber-uns/projekte/erschliessung-und-digitalisierung-der-wasserzeichen-in-den-musikhandschriften-der-bayerischen-staatsbibliothek-bis-zum-ende-des-17-jahrhunderts/

Záznam o rukopisu D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154 v databázi RISM

https://opac.rism.info/metaopac/search?View=rism&documentid=456052096

Struktura složek rukopisu D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154

https://www.wasserzeichen-online.de/wzis/lagenschema.php?datei=DE5580-Musms3154

Digitalizované filigrány rukopisu D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154

https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0011/bsb00118745/images/index.html?fip=193.174.98.30&seite=1&pdfseitex=

A musicologist swims in watermarks

Lenka Hlávková

Musical sources from the late medieval period preserved in domestic libraries and archives are largely unexplored, both in terms of their content and of their material aspect. Unless a researcher chooses a specific manuscript for detailed monographical study (or unless the given title was entrusted to a musicology student as a source for a diploma thesis or dissertation), even in this time of advanced digital archival of watermarks, we only have approximate dating for most musical sources. Within the „Old Myths, New Facts“ project, we try to overcome this deficiency at least for key manuscripts, as without reliable dating, we can hardly bring new insights of historical nature.

Between July 1st and 4th 2020, I attended the annual MEDREN (Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference), this year in cyberspace instead of Edinburgh, and already on the first day my attention found itself caught by a contribution from colleagues from the Bavarian State Library in Munich. This institution is a pioneer among digitization of (not only) musical sources and in a recent project Erschließung und Digitalisierung der Wasserzeichen in den Musikhandschriften der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek bis zum Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts, it went from making digitally available the content of musical manuscripts towards also providing metadata about their physical aspects. Principal Investigators Dr. Veronika Giglberger and Bernhard Lutz talked not only about using thermography to obtain images in a careful way, but also more broadly about the methodology of the project. Each of the 170 manuscripts in question underwent detailed codicological analysis, which is one of the main reasons why researchers request expediting an original source, and at the same time a point where the protection of historical material comes in conflict with the need for its scientific reflection. In the next step, watermarks were digitized and after some further technical processing the records published at the Bavarian State Library were connected to existing databases (Wasserzeichen-Informationssystem, RISM). All such information about the manuscripts is therefore available online and I imagine the hearts of all musicologists who have ever been tempted by their research towards their own analysis of physical sources (and thus encroach territory traditionally held by codicologists and the like) must beat all the faster with excitement!

How are we faring in the Czech Republic? So far we hunt watermarks with copy paper, a soft pencil and a cold-light lamp, some technically more competent colleagues take photos and then adjust contrast settings to make watermarks at least a little visible under dense handwriting. Despite considerable craftiness and the enterprising spirit therein, professional thermographic images are impossible to beat. If there did exist a database mapping watermarks in manuscripts (not just musical ones) archived in the many institutions in the Czech Republic, ideally within the existing international systems, and with data collected using the same technology, historically oriented fields would definitely welcome the ensuing possibilities. With the increasing volume of database entries, one can not just date a manuscript more accurately, but also gather information about its historical context. For instance, if paper is found in a Czech manuscript that is clearly of Italian origin: has the paper been imported from Italy with the compositions already copied? Or was it possible to buy this paper in Czech lands? Is it a hint that certain institutions had been in contact with each other? To such questions we seek answers using other means currently at our disposal, but it seems that if we could close the gap with our Bavarian colleagues and apply their tried-and-tested methods on the physical artifacts we have, would not the next level of Europe-wide insight warrant phasing out the perhaps romantic rituals of stocking copy paper and sharpening pencils for the watermark hunts of yesterday and, as of yet, today?